Introduction

Mass digitization has become a fact of life at most major University Libraries in recent years. In the case of printed books, initiatives like Google’s and the the Internet Archive’s produce page images with attached metadata. These are OCR’ed and processed to make them searchable and readable via a web browser and (in the case of the IA) in a variety of other formats, such as PDF. These processes do not accommodate documents for which OCR is currently impossible however. Handwritten documents can, and are, regularly digitized, but human beings must produce transcriptions for them (if this is done at all) and the transcriptions are typically linked to the images only on the level of the page.

This project began as an attempt to see what could be done in an automated or semi-automated way to allow linkage between transcription and image at a deeper level and also annotation of the image at the level of the text on the page. Transcription of the text in a page image can be considered a special case of annotation.

UNC Chapel Hill is contemplating a very large scale manuscript digitization project, potentially covering the entire Southern Historical Collection. The Carolina Digital Library and Archives (CDLA) also has an ongoing, smaller, manuscript digitization project funded by the Watson-Brown foundation and several completed projects published under its Documenting the American South program which deal with manuscript images and transcriptions in TEI.

There are a number of existing tools that provide for user-controlled image annotation. This is typically accomplished by providing the user with drawing tools with which they may draw shape overlays on the image. These overlays can in turn be linked to text annotations entered by the user. This is the way image annotation works on Flickr, for example, and also the IMT. The TEI P5 facsimile markup conceives of text-image linking in this fashion also.

Drawing rectangular overlays on top of an image is a good compromise between ease-of-use and utility, and rectangles fit well with most types of written text. It does prompt the questions of whether it is possible to go deeper, however, and what to do with lines of text that aren’t able to be captured by rectangles. I noted with interest the proof-of-concept work my colleagues Sean Gillies and Tom Elliott did earlier this year using the OpenLayers Javascript library as a means of tracing text on a sample inscription[1]. The vector drawings overlaid on the image are serialized as SVG which can then be saved and used as a linking mechanism. Inscriptol was the inspiration for the work presented in this paper. Some further discussion about tools for text and image linking took place on the Stoa site at the same time.[2] The starting point for the experiments described here is a tool for tracing raster images and converting them to vector graphics named potrace[3]. Potrace will convert a bitmap to SVG, among other formats. It is licensed under the GPL. Tests with the tool on manuscript pages were promising, so I decided to see whether a toolchain could be constructed, using only Free, Open Source software, that would start with a manuscript image in a standard format such as JPEG and take it into an environment where the image could be linked to a transcription.

The Toolchain

The goal of this experiment is to see whether it is possible to go from a page image and a TEI-based transcription to a linked presentation of the two, using only Free, Open Source tools. In addition the experiment is intended to evaluate the extent to which this process might be automated and, conversely, where and how much human intervention will be required in the process.

Image preparation

The process of tracing a raster image to produce a vector analog requires a bitmap format as input. The source images in DocSouth are most likely to be either TIFF or JPEG, so they must be converted to a source usable by potrace. The convert utility that comes with the open source image processing library ImageMagick[4] performs this function with ease using a command such as:

convert mss01-01-p01.jpg mss01-01-p01.pnm

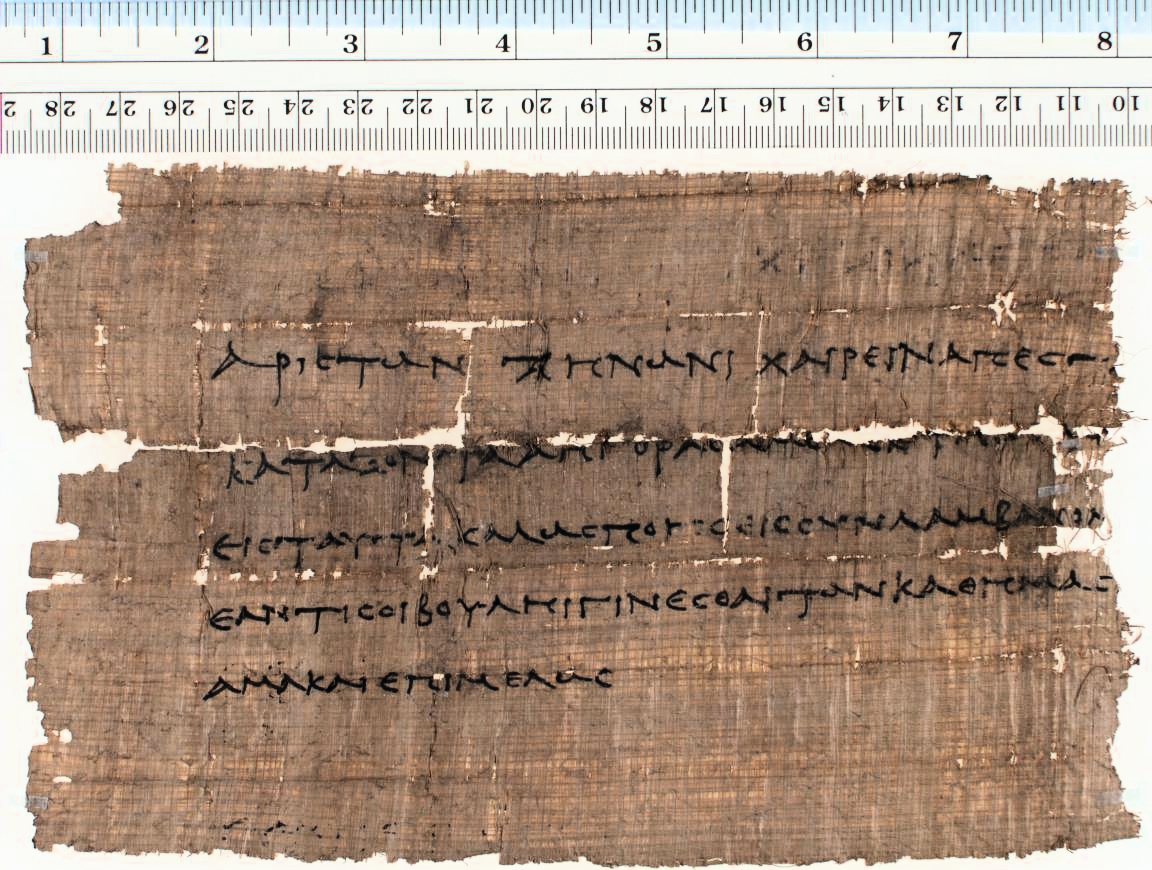

Figure 1

Papyrus (P. Mich. 1.78)

ImageMagick also supports a wide variety of additional image manipulations, and is likely to prove useful in other kinds of image preprocessing. As we work on refining the techniques outlined here, it is likely that operations such as image sharpening and increasing the contrast will be added to the preprocessing pipeline in order to produce sources that potrace can do a better job of converting.

Conversion to SVG

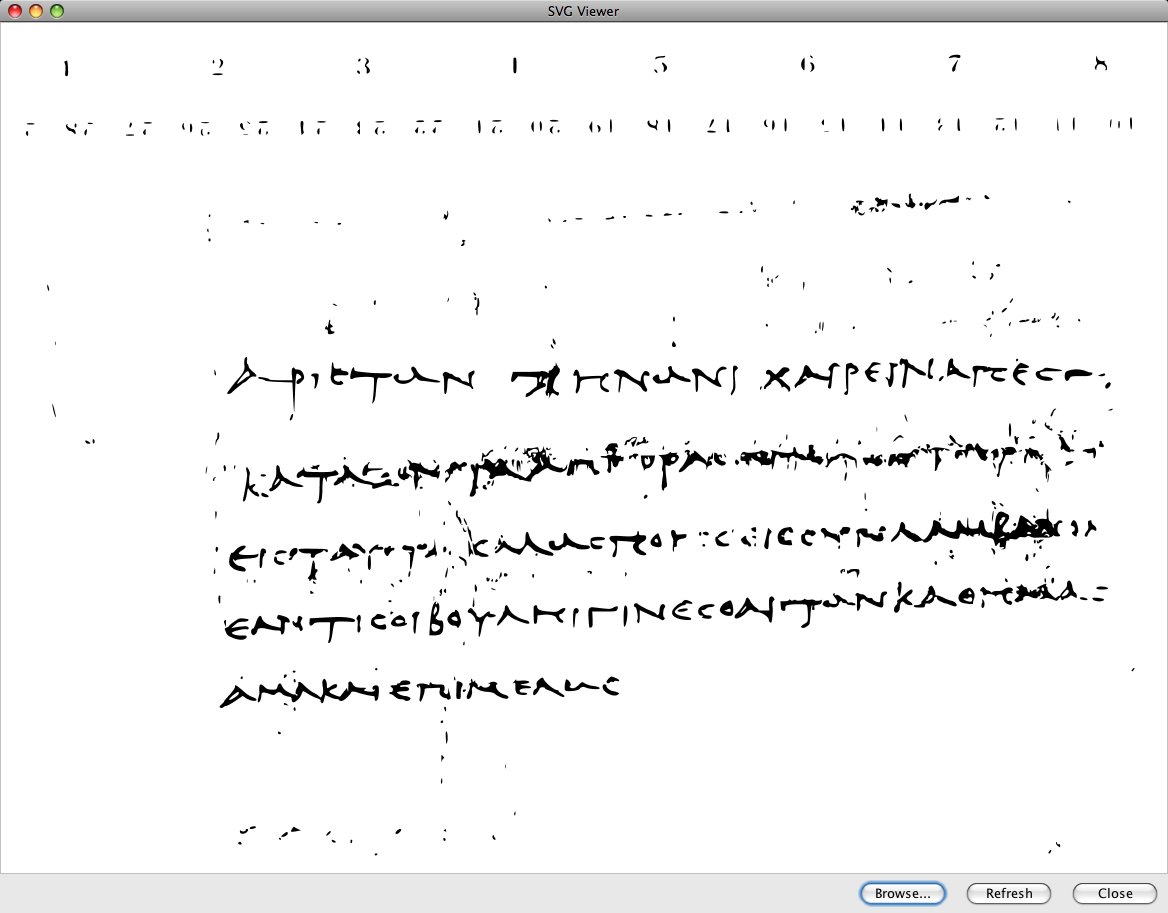

Potrace handles the conversion from bitmap to SVG, as part of the process, it collapses the image’s color space to 1 bit (black/white) and then creates vector paths tracing the black shapes in the image. Setting the cutoff at which it determines whether a pixel becomes black or white is one of the main steps at which human intervention is presently required. In experimenting on a number of images, I was able to obtain good results after a period of trial and error.

The image in figure 1 was converted to the image in figure 2 using the following command:

potrace -s -t 4 -k 0.3 -G 2.5 P.Mich.inv.\ 3088.pnm

Figure 2

Figure 1 after conversion to SVG

Potrace produces an SVG document with paths that look like

<path d="M5471 5212 c-1 -13 -5 -20 -11 -17 -5 3 -10 1 -10 -5 0 -14 -25 -40 -39 -40 -6 0 -11 -7 -11 -16 0 -12 -4 -14 -12 -7 -16 13 -67 22 -72 14 -2 -3 -67 -6 -144 -6 l-139 0 -12 -44 c-17 -62 1 -78 37 -34 l27 33 93 -4 c51 -2 95 -6 98 -9 11 -11 6 -91 -6 -95 -6 -2 -27 -17 -45 -33 -18 -16 -37 -29 -43 -29 -12 0 -24 -29 -16 -41 4 -8 58 21 74 41 11 14 100 60 114 60 9 0 16 8 16 20 0 11 -7 20 -15 20 -8 0 -15 6 -15 14 0 15 30 44 30 30 0 -5 4 -2 10 6 5 8 12 11 15 8 4 -4 3 -13 -1 -20 -5 -7 -10 -35 -11 -63 -1 -27 -6 -51 -11 -53 -11 -3 -3 -52 9 -52 5 0 9 7 9 15 0 8 4 15 9 15 4 0 6 -12 4 -27 l-4 -28 16 28 c18 32 23 32 54 11 19 -14 25 -14 31 -3 10 15 4 29 -13 29 -7 0 -21 9 -31 21 -16 19 -16 27 -5 71 6 28 20 59 31 70 30 30 40 65 23 82 -9 8 -19 25 -24 38 l-10 23 0 -23z m-146 -149 c-8 -32 -13 -39 -21 -30 -10 9 5 57 17 57 7 0 9 -10 4 -27z"/>They use SVG’s moveto (m), cubic bézier curveto (c) and lineto (l) commands in relative mode, that is the first moveto command determines the start point of the path, and then subsequent coordinates are relative to that point. This mode is obviously a convenient notation for a program creating the paths, but it is less convenient for working with the paths, so a conversion to the absolute notation is necessary. In addition, the SVG output by potrace is marked as version 1.0 (although it is compatible with the current standard, 1.1) and the paths need to have ids assigned to them so that they will be able to be referred to later.

SVG Cleanup

The SVG editor Inkscape (which in fact uses potrace internally to trace images) may be used from the command line to output a version of the SVG with the relative path notation converted to absolute. If invoked with the -l parameter, Inkscape will output a ‘plain’ SVG file without the additional namespaces the program typically adds. For example:

inkscape -l P.Mich.inv.\ 3088.svg P.Mich.inv.\ 3088.svgXSLT was used to insert id numbers and do additional small pieces of cleanup, including the removal of a duplicate SVG namespace and setting the version number to 1.1. After processing, an example a path looks like

<path d="M 88.96875,276.20312 C 88.96875,276.89375 86.36875,280.42813 85.271875,281.2 C 84.825,281.48438 84.5,281.93125 84.5,282.175 C 84.5,282.37813 84.0125,282.94687 83.44375,283.39375 C 82.753125,283.9625 82.55,284.36875 82.834375,284.65312 C 83.321875,285.14062 86.978125,283.51562 90.065625,281.40312 L 92.178125,279.98125 L 93.4375,280.875 C 95.021875,282.0125 97.90625,282.45938 97.90625,281.60625 C 97.90625,281.28125 97.25625,280.79375 96.403125,280.55 C 95.55,280.30625 94.371875,279.65625 93.7625,279.16875 C 89.171875,275.30937 88.96875,275.1875 88.96875,276.20312 z M 90.390625,279.33125 C 90.146875,279.98125 87.34375,281.6875 86.571875,281.6875 C 86.2875,281.6875 86.9375,280.875 88.034375,279.85938 C 89.821875,278.15312 90.91875,277.90938 90.390625,279.33125 z" id="path13332"/>

SVG Analysis

At this point, we have an SVG document that is ready for analysis. The initial

experiment uses a Python script that simply attempts to detect lines in the image

and to

organize the paths within those lines into groups within the document. The paths are

sorted

left to right and top to bottom and then merged using a simple algorithm. The process

starts

with the bounding rectangle of the leftmost, topmost path and looks at the next path’s

bounding rectangle. If they overlap top to bottom more than 45%, then the two are

merged

into a group. This continues until no more overlapping rectangles can be found, and

the

remaining paths that have not been assigned to a group are passed to the function

again. The

process repeats until all paths have been assigned to a group. When analysis is complete,

the Python script writes the results out to disk in two formats. Initially, the script

produced an SVG file with grouped paths and with bounding rectangles inserted to make

the

boundaries of the line groups visible.

Figure 3 SVG with the original image embedded, after line detection.

Display

I noted above that the proof-of-concept work on tracing inscriptions by Elliott and

Gillies used an Open Source map display library called OpenLayers as the basis for

its

display and annotation capabilities. OpenLayers allows the insertion of a single image

as a

base layer (though it supports tiled images as well), so it is quite simple to insert

a page

image into it.

Figure 4 OpenLayers with embedded image and transcription Figure 5 The layers in the image viewer.

The experimental system discussed here adds several functions to the OpenLayers library in order to support paths and groups of paths. OpenLayers represents vectors in the browser using either SVG or VML, depending on the browser’s capabilities. This test only attempted to display the traced text in Firefox and Safari, both of which have SVG support, so only the SVG serialization code was modified. In theory, the VML generation code should support similar functionality, but this has not been attempted. OpenLayers provides a very useful platform for display because it has built in functionality like zoom and pan, as well as the ability to turn layers on and off and to add event handlers for structures it draws. This enables, for example, highlighting to be activated when the mouse hovers over a line.

After the functions to store path data and serialize it as SVG were added to OpenLayers, the Python script was modified to output instructions to OpenLayers in Javascript that draw the paths and bounding rectangles as separate layers on top of the image. OpenLayers can, as described above, enable the addition of even handlers to polygon features, so in order to demonstrate the ability to link the grouped vectors to lines in a transcription, I matched path group ids to their corresponding line number using a pair of JSON objects (e.g. fig. #)

var img2xml = {

grpath168: ["ln0", "ln1"],

grpath282: ["ln2"],

...

grpath3426: ["ln26"],

grpath3626: ["ln27"]

};

The event handler for a mouseover on one of the rectangles bounding a line of text

calls

a function that changes the color of the paths within the line and the stroke of the

bounding rectangle itself.

Figure 6 Hovering over a line in the image. Figure 7 Hovering over a line of text.

Conclusions

The experiments outlined above prove that it is feasible to go from a page image with a TEI-based transcription to an online display in which the image can be panned and zoomed, and the text on the page can be linked to the transcription (and vice-versa). The steps in the process that have not yet been fully automated are the selection of a black/white cutoff for the page image, the decision of what percentage of vertical overlap to use in recognizing that two paths are members of the same line, and the need for line beginning (<lb/>) tags to be inserted into the TEI transcription (if it does not already contain them). The tools employed to produce the SVG tracing and the interactive display are all stable and well-supported (although the path support added to OpenLayers needs additional work). It seems clear that additional testing and the attempt to produce a working implementation will be well worth the effort.

Where to go from here

One question posed by the apparent success of the method is what should link to what. What structures in the vector graphics document can be detected (beyond lines) and how should they be linked to the transcriptions? There are some very thorny concurrency issues here, since ink from one letter may touch another, and thus form a single path consisting of multiple letters, making it impossible to isolate letters, or even words if the letters belong to different words. A descender on the letter ‘f’ might touch a letter in the line below, making it impossible to easily identify the two lines as separate. These difficulties mean that linking word for word or letter for letter between documents is not necessarily possible. The streams are not parallel. Of course, vector paths can be sliced, and the image and text streams therefore could be made parallel, but this kind of operation will almost certainly require a human being with an SVG editor such as Inkscape. A second, related issue is that text transcriptions in XML may well define document structure in a semantic, rather than a physical way. Line, word, and letter segments can be marked in TEI, but they frequently are not. The DocSouth example used as a test case here does not have line breaks marked, for example.

The mechanism used for linking bears further thought and study. The current implementation hand waves over the problem, simply mapping an id in one document to one or more ids in the other and vice versa using JSON. It would be much better to develop a standard for this kind of linking, since there is no guarantee that the id from one document would easily be available to the other. TEI P5 envisions the alignment of different document streams of this type using a link group [5]. Using TEI for this is a possible solution, but it does involve changing the TEI document, which may not be desirable. As the P5 standard remarks: “If it is not feasible to add more markup to the original text, some form of stand-off markup will be needed.” Stand-off markup seems a better solution in the abstract, but it isn’t immediately clear what is the best way to implement this solution.

The proof-of-concept system illustrated above attempts to detect lines only, and that in a very simple way, by looking along the x-axis for overlapping structures. Probabilistic methods may well prove the best way to determine whether any given path belongs to the same group as another path, or whether a previously constructed group really holds together. The algorithms for structure detection therefore need a great deal of refinement and it is not yet clear how deep it is possible to go in detecting structure within the SVG image automatically. How much human intervention can be asked for, provided, and enabled within this framework is an important question too. OpenLayers provides some limited vector editing capabilities, but how reasonable is it to ask a user to manually split, for example, two lines that have mistakenly been combined into a single group?

The prospects for further development of this idea seem rich. I hope to proceed by further developing and refining the structure detection routines, by refining the display capabilities of the web interface and improving and standardizing the linking mechanisms. I plan to seek grant funding to work on this in the context of one or more of UNC Library’s digitized manuscript collections later this year.

References

[APIS1769] Advanced Papyrological Information System, "APIS record: michigan.apis.1769," http://wwwapp.cc.columbia.edu/ldpd/app/apis/search?mode=search&institution=michigan&pubnum_coll=P.Mich.&pubnum_vol=1&pubnum_page=78&sort=date&resPerPage=25&action=search&p=1

[DSTrue01] Documenting the American South, "Letter from John and Ebenezer Pettigrew to Charles Pettigrew," http://docsouth.unc.edu/true/mss01-01/mss01-01.html.

[PMich1.78] Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri, "P.Mich.: Michigan Papyri 1.78," http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.05.0163;layout=;query=1%3A78;loc=78.

[Gillies2008] Gillies, Sean, "Digitizing Ancient Inscriptions with OpenLayers," (blog post) http://sgillies.net/blog/691/digitizing-ancient-inscriptions-with-openlayers, February 21, 2008.

[OL2.6] "OpenLayers, v. 2.6," http://openlayers.org. Release notes for v. 2.6 at http://trac.openlayers.org/wiki/Release/2.6/Notes.

[Selinger1.8] Selinger, Peter, "Potrace, v. 1.8," http://potrace.sourceforge.net/.

[Selinger2003] Selinger, Peter, "Potrace: a polygon-based tracing algorithm," http://potrace.sourceforge.net/potrace.pdf, September 20, 2003.

[Terras2008] Terras, Melissa, "Palaeographic Image Markup Tools," (blog post) http://www.stoa.org/?p=776, February 19, 2008.